Chinese Property and the Problem of Household Saving

A decline in property values may not crash the economy but it could generate stagnation

With Evergrande in the news many are taking a fresh look at the Chinese property market. The Chinese property market has been a favourite of market bears for well over a decade. It is not hard to see why. By any standard metric the sector is vastly overleveraged and overvalued.

Here are Chinese house price-to-income ratios by city from 2020.

Now compare these with the same metric for the United States.

As we can see, the US series is currently registering a reading of around 7 — and by historical standards this makes it look like the US market is in a bubble. A reading of 7 in China, however, is just a little higher than the median city. The truly bubbly cities like Beijing and Shenzhen are well over double the US as a whole.

These are truly eye-watering house price-to-income ratios. At a certain point, housing will simply become too unaffordable for the average working person. The Chinese government has recognised this and is now seeking to make housing more affordable.

Most bears are focused on the fact that this could lead to a slowdown in investment spending in the construction sector and could lead to an economic crash. This is a possibility. But we must always remember that the Chinese economy is not really a market economy. Consumer goods are distributed by the market, yes; but investment spending is controlled by the state through their banking system.

For this reason, if they shutdown investment in the construction sector they can simply turn on the taps in another sector — light industry, perhaps, or, if there really is nothing left to build they can beef up military spending. It would be very surprising if the Chinese leadership had not considered this problem and planned accordingly.

But there is another problem that few are talking about. It relates to the issue of household savings. China has some of the highest household savings in the world. Chinese households save around 35% of their disposable income. Developed economies at the high-end of the spectrum do not even have savings rates of 20%. China is not just an outlier, it is an extreme outlier.

The reasons for this are simple enough. China lacks a solid welfare state. When China was a truly communist economy, welfare was deployed via state-owned factories and businesses. But as these business were closed down, or turned into more modern state industries, their welfare arm was closed down.

For this reason, Chinese households squirrel away savings as a safety measure in case of economic or personal financial turmoil.

This is why the Chinese economy is so reliant on heavy investment expenditure. A high household savings rate means, by definition, a relatively low consumption rate. And if consumption is low, to grow the economy needs constant high levels of investment expenditure.

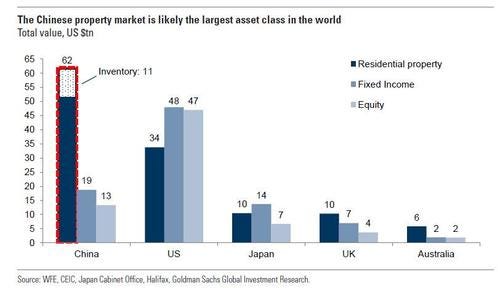

The problem here is that housing makes up the majority of household net worth in China.

If the prices of housing comes down, the average Chinese household will see an enormous decline in their net worth. This will likely scare them and induce them to save even more than they do now.

This could put a dent in the Chinese government’s desire to switch the economy from a high investment economy into a high consumption economy. The Chinese have gotten themselves in a bind. They have become addicted to high rates of investment that have impacted every aspect of the economy in ways that were likely not predicted. Winding down this reliance on heavy investment might be more difficult than policymakers currently think.