Yesterday it was announced that Germany will consider gas rationing as a response to a potential embargo against Russian energy imports. This seems to me an… unwise… policy, but more on that later. First let us look at what the potential impact would be on German CPI.

We start the analysis by stripping out the two large components in the German CPI most likely to be impacted: ‘Electricity, gas and other fuels’ and ‘Fuels and lubricants for vehicles’. Both of these are strongly correlated with German CPI.

We run a quick multivariate regression to ensure that they are both having independent impacts.

Yes, indeed they do. So we will include them both in our model.

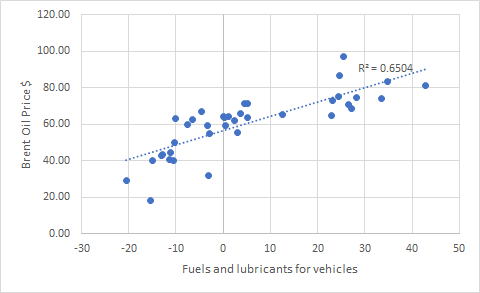

Okay, how should we model these components? Let’s try using the oil price.

Great, that looks promising. In a previous post I modelled a German energy embargo by assuming a $220 a barrel price by the end of 2022. Note that this does not have to mean literally a $220. It just means that an embargo would hit German prices as if the price has hit $220.

Even if the price didn’t hit this — due to rationing/blackouts etc — the price impact should, in theory, be largely the same. Think of rationing as a quantity adjustment rather than a price adjustment — and since both put pressure on the overall production and distribution process, let’s assume they have a roughly similar impact.

Here is what happens to those two components.

Next, we construct a multivariate model for the CPI as a whole. I have included the entire model output to show just how credible this model is — and how much faith we can put in it assuming that our $220 oil price assumption is reasonable (RSQ = ~0.95 will do that).

There you have it: German CPI hits 15% by year end.

As alluded to at the top of the post, this is not a wise policy. In fact, it is downright crazy. The aim of the embargo is to hurt Russia. Germany makes up around 11% of Russia’s oil exports and around 16% of its natural gas exports. Which is worse? A temporary loss of around 10-15% of your energy exports — no different to the Russians than seeing a 10-15% price decrease in oil? Or spiralling inflation? I’ll take the temporary loss of 10-15% of energy exports, thank you!

Beyond this what does the policy ‘do’? Would it force the Russians out of Ukraine? Not a chance. Would it even give the Ukrainians a bigger stack of chips at the bargaining table? Not that I can see. As I said, a 10-15% decline in energy exports is roughly equivalent for Russia as a 10-15% decline in the price of oil. If I were the Russians, I wouldn’t care much about this. And as I explained in a previous post, if the embargo drove oil prices skyward due to secondary market effects — i.e. Germany trying to poach on other countries’ imports — the price increase would likely negate the fall in quantity sold.

So, why would Germany contemplate such a self-destructive and reckless policy? I see two possibilities.

Policymakers really have become reckless. Two years of lockdown interventions have made policymarkets across the world blasé about extreme interventions in the economy. Policies that would have been unthinkable five years ago — due to the economic damage they would cause — are now considered reasonable.

This is a ‘feint’, as the military strategists say. German policymakers can see that talks between Russia and Ukraine are making progress and they expect a ceasefire soon. Because of this, they feel able to make threats that they have no intention of carrying through.

Let’s be generous and assume that the second reading is the correct one. There are still enormous risks. Germany has put this option on the table. Once on the table, it is hard to take off. What if their reading of the negotiations is wrong? Or what if something happens on the ground in Ukraine that derails the talks? In war, high uncertainty is the rule, not the exception. In such a scenario German policymakers might find themselves boxed in and forced by circumstance to use the option that they only put on the table as a feint.

I hope the normally sober German financial and economic community are paying attention. Last time we got uncontrollable inflation in Germany, it didn’t work out so well.

A good article, overall...but there are a couple items worth raising...

First...

The 10-15% reduction in Russian oil demand isn't really the same as a 10-15% reduction in the oil price. The latter would motivate other oil producers to reduce their supply. The former may not lead to increased oil supply from the other players - but would certainly not reduce it. OPEC+ has held the line on increasing their output (their repeated failures to meat monthly prod. quotas is telling) - but will that discipline really hold in the long-term? Especially in the wake of demand destruction? (see next)

Second...

When oil prices really surged in 2007-2008 - demand proved quite inelastic. We are already seeing early signs of demand destruction in the USA and a couple of Asian economies. Obviously, we are seeing *significant* demand destruction out of China at the moment due to the lockdowns. On the one hand, China has always been equal to the task of containing COVID outbreaks during the past two years. But ever-more-infectious variants have made outbreaks and lockdowns more frequent - and it isn't exactly evident how they extricate themselves from that loop here. Perhaps the real implication here is a question of whether the reduced demand is contained on the consumer side - or if it necessitates reduced industrial output. We'll see.