How predictable was the recent inflation?

Most people doing serious data work have now concluded that the current inflation is mostly a supply side problem. The latest release in this regard was this excellent piece by some New York Fed economists.

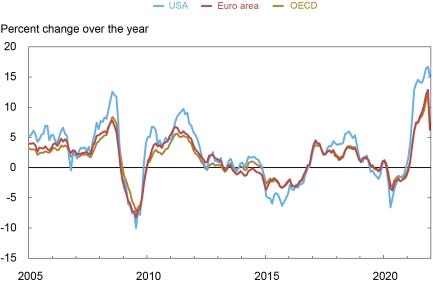

They show two pieces of compelling evidence that this is a supply side problem, first and foremost. The first is that inflation — both PPI and CPI — are highly correlated globally.

Given that different countries and regions have different demand-side policies in place at any given time, a convergence of country-level inflation on global inflation indicates that supply problems may be afoot.

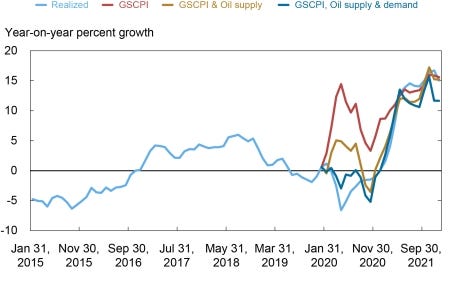

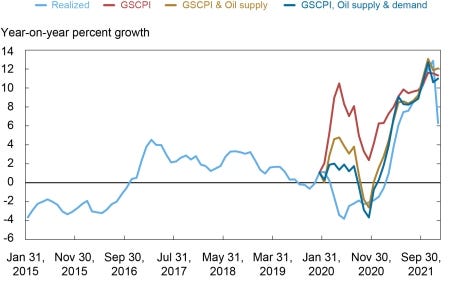

The authors firm up this insight by showing that energy and global supply change pressure indices (GSCPI) are correlated with both US PPI and European PPI. (In the piece they show the same for PPI).

Yet the economists lag behind this clear quantitative work. The debate on inflation amongst the policy guys and the popular writers seems focused on demand-side issues. Larry Summers is out making the case that the inflation is due to government spending and that interest rates should be higher. Economists are now ‘responding’ to Summers as a sort of totem of what the argument should be.

The increased government spending is not going to help with these sorts of supply problems, rather it will exacerbate them. And the question of how the Fed should respond is an open one. But ignoring the supply-side and focusing on the demand-side is bizarre. It speaks to a profession that has, due to recent history (or political inclination), become obsessed with the demand-side. Last time that happened it didn’t work out well. See: the 1970s and the rise of monetarism.

So, the state of play right now is not so good. Especially given that the supply-side crisis could well be reaching a more intense phase — with truckers seeking to shut down supply chains in North America and now maybe even in Europe. Economists need to pull the finger out and get it together.

A related question is: how predictable was this inflation and when was it possible to make a call on it? I would say that it was very predictable and only required the most basic macroeconomics knowledge — basically that of a competent undergraduate. When was it possible to make a call on it? That was a little more complex. Let’s start with its predictability.

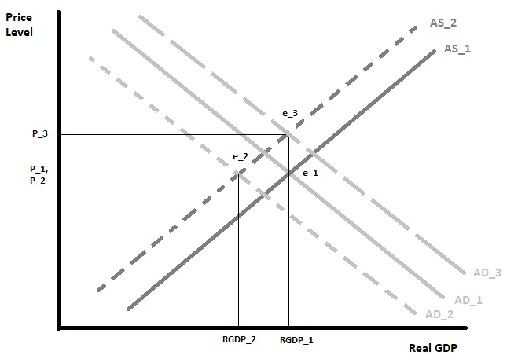

Since the pandemic started in March 2020 I have been passing around this very simple diagram.

This is a simple AS-AD model, taught to macro undergrads. I’ve always thought it a stretch to even call it a ‘model’ per se. It simply shows that if aggregate demand — that is, all demand in the economy — outstrips aggregate supply, then prices will rise. Intuitively, if there is $100 of spending in an economy, and 100 units of goods valued at $0.80 apiece in yesterday’s prices, then the goods must rise in price to $1 apiece due to the spending and the supply of goods not matching.

The AS-AD model above is laid out in a way that describes what happened during the lockdowns. Here is my explanation.

We start before the lockdown at the equilibrium e_1. We then have a simultaneous collapse in both aggregate supply and aggregate demand due to the lockdown and the closures and income losses associated with it. This leaves us at equilibrium e_2. Here we see that, although real GDP has shrunk, prices remain stable. The assumption here is that the shop closures, etc., are matched by the income losses from laying off staff, etc. The result would be a major contraction in economic activity – a recession – shown by the fall from RGDP_1 to RGDP_2.

The stimulus that is being deployed to counter this recession aims to replace the lost demand. We have represented this as the aggregate demand curve AD_3. To get back to RGDP_1 – that is, the initial level of economic activity – the AD curve must be pushed further out to the right. This results in meeting the new AS curve at a much higher price level – prices have shifted from P_1 to P_3. Hence, we arrive at the conclusion: if there is a simultaneous supply and demand collapse in the economy, in order to prevent the economy from falling into a major recession stimulus will have to be deployed that will result in a higher price level.

What did this simple exercise tell us? It told us — I would argue as soon as the consequences of the lockdowns became clear, which was effectively immediately — that we should be very cautious about an inflationary outburst.

A caveat here. Much in macroeconomics is controversial. And I myself have controversial views on many topics. But the basic intuition of the AS-AD model — I mean the most basic intuition that we have used above — is not controversial so far as I know. All ‘schools’ of economics agree with this intuition. Debate takes place at one or two steps higher in the modelling. I say this to emphasise that, if this was obvious to me, and this is taught in undergrad classes, then every economist should have arrived at this conclusion.

So, even in March 2020 every economist who understands basic macro should have had their feelers in the air for rising inflation. The next question then: when was it ‘calleable’?

Good forecasters know how difficult it is to forecast. They are humble in what they know and cautious of what they do not. We had never seen lockdowns and vaccine mandates before, so we did not know what to expect. The reasonable position then — at least, what I thought to be the reasonable position — was to wait for the initial supply-side signs to manifest themselves before ringing the bell in the town square and barking about inflation.

When was it reasonable to make this call? I would argue that the supply-side problems were clear enough to make the call that inflation was the most probable outcome in early-to-mid September and I wrote an essay to that effect in Moneyweek.

Clear price signals — especially in used car markets — were available before that date. I believe these were doing the rounds in July and August. Some analysts thought they were definitive. I thought they were highly interesting but not quite definitive. Anyway, whatever position you took on that, inflation should have been the baseline scenario for any close observer by late-summer, early-autumn of 2021.

Markets did not respond to the inflation in September. Even in November they were cautious about rate hikes — although there was a lot of discussion in markets in this period, which at least meant that they were processing the trends. By December, the markets had come around to seeing that inflation was the baseline scenario. There is also a wide appreciation in markets that this is primarily a supply-side problem — hence the creation of the GSCPI and related indices — but I do not believe the markets fully understand the consequences of this, as I have written about in Newsweek.

The academic, policy and popular economists are completely lagging behind though. They simply will not look at the supply-side and take it seriously — just as many would not look at mortgage-lending prior to 2008. Why is this? That would require a whole other post. But it is a fascinating trend. And one much worth watching, as these guys and girls influence policy.