Today I’m going to look at another potential inflation-hedging strategy in the foreign exchange markets. The idea is pretty straightforward: we find a small country that depends on exports to a larger bloc and also tends to be more prone to inflation than that bloc. Then we short that currency.

Hungary provides a perfect example. Hungary exports a huge amount of manufactures to the rest of Europe. To a large extent these are automotive parts. German industry uses cheaper Hungarian labour to make many of the simpler components and then assesmbles these in Germany.

Hungary had enough foresight not to adopt the euro. If they had their economy would still be broken. But since they have the forint, they are able to ensure that rising nominal labour costs do not make their goods less attractive. Let’s look at how this works.

Here is a regression in which the dependent variable is Hungary’s current account balance and the explanatory variables are the growth in Hungarian unit labour costs and the real effective exchange rate.

As we can see, these determine a very large proportion of the Hungarian current account — around 70%.

The chart below shows how the real effective exchange rate and the current account balance have behaved through time.

As we can see, up until 2008 or so the Hungarians allowed their exchange rate to strengthen. This made Hungarians feel richer if they travelled. But it also led to enormous current account deficits. These deficits eventually destroyed the Hungarian economy as everything unwound during the ensuing financial crisis.

But the Hungarians learned from this. After 2008 they started allowing the forint to decline. This negated any increase in domestic labour costs and kept Hungary competitive. The effect has been a tendency for Hungary to run current account surpluses.

Here’s the thing though: Hungary tends to have a higher rate of inflation than the Eurozone.

But, because the Hungarians are smart about their foreign exchange policy, this differential is allowed to drive the HUF/EUR exchange rate.

This means that investors should be able to invest in EUR/HUF as an inflation hedge. We simply assume that if inflation takes hold and it is worse in Hungary than it is in the Eurozone, then the Hungarians will allow the HUF to decline in value relative to the EUR.

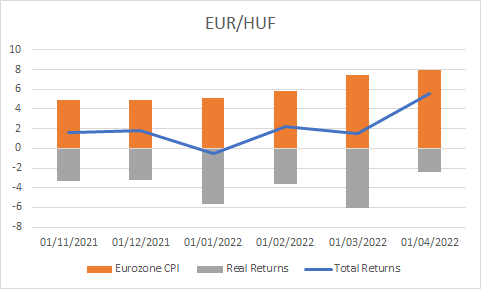

How has this investment gone so far? Here are the recent returns.

So, being long EUR/HUF has certainly paid. But it has not yet generated real returns over Eurozone CPI. Why? Scroll back up and look at the chart with the Hungarian current account. In recent years, the Hungarians have allowed their current account to slip back into deficit.

The reason is simple enough: they need to be more aggressive on devaluing the forint. Of course, investors looking to protect their portfolios against inflation can help them in that regard! But it would be nice if the government and the central bank paid closer attention to their current account and talk down the forint a bit more. If they do, EUR/HUF should become an even better inflation hedge. Worth watching.