With inflation ticking over at a decent pace and supply chain shortages showing no sign of easing, interest rate rises are being discussed. Last week I looked at the potential economic implications of this. This week I want to briefly consider some short-term investment implications.

Interest rate hikes are often followed by recessions. Conventional wisdom has it that you should own bonds going into recessions. The dynamics run something like this: the central bank raises interest rates; this is initially a negative for bonds, as their price falls; but at a certain point, the interest rate hike generates a recession and the central bank is forced to reverse course; at this point, you should own bonds as you will catch the price increases on the way back down to lower rates.

In addition to this, stocks often fall as the economy enters recession. So, in recessions even cash holdings are preferable to stock holdings. Cash allows you to keep your powder dry and buy up cheap stocks after the market declines. Bonds ‘turbocharge’ this effect by giving you short-term gains at the same time as stocks fall and become cheaper. Given the effect of compounding — especially when buying stocks at the bottom of the market — even a small gain in bonds as stocks are falling can mean significantly higher returns over the next 5-10 years.

Does this conventional wisdom have empirical support, however? Short answer: it depends on your benchmark. To illustrate this, let us take as our benchmark average bond returns.

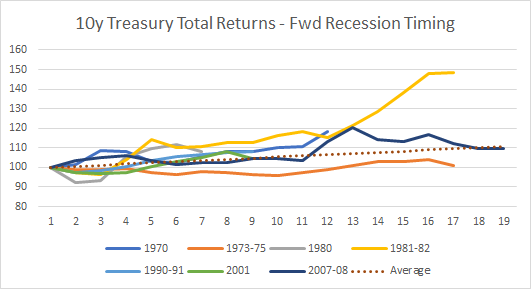

We will first look at bond returns during recessions. Here we use the NBER recession indicator. We assume that investors know that the economy is currently in a recession and buy bonds at that moment. They sell when the economy exits the recession.

As we can see, it is a mixed bag. Bonds do typically make gains in recessions, but they only make excessive gains sometimes.

Being able to predict the recession ahead of time — in our example, a month ahead of time — has investors faring no better. In fact, buying bonds a month ahead of a recession and selling them in the recovery month is worse than simply buying them when the economy is in recession.

Still though, most of the time bonds do make positive gains in recessions. This means that the conventional wisdom is usually right: you are better off having bonds during a recession than you are holding cash. There is the potential for a ‘turbocharge’ to returns, even if it is not vastly better than just holding bonds across the cycle.

But what if we focus less on the economy and more on the bond market itself. It is well-known that rate hike-driven recessions are often precipitated by an inversion of the yield curve — that is, when short-term bond yields rise above long-term bond yields.

What if investors simply focused on yield curve inversion an invested accordingly? Such a strategy would have the added convenience in that the investor would not have to predict a recession; he would only have to look at what is currently happening in bond markets. Below we show the data since the late-1980s, when central banks started inflation-targeting and this effect became relatively reliable.

Here we see even more promising results. By simply buying bonds when the yield curve inverts and selling them when the yield curve reverts to normal, the investor will often get not only positive returns, but positive returns that are substantially higher than average bond returns.

Apart from in 2006-08, when we experienced an unusually long yield curve inversion, bonds reliably gained around 10% in the first 6 months of yield curve inversion and 15% in the first 12 months. These gains are easily enough to turbocharge future gains in stocks bought cheaply.

If markets stubbornly refuse to come down, on the other hand, the returns in bonds in these situations are easily enough to offset the gains missed out in the stock market. Investors in bonds during inverted yield curve events are unlikley to experience the dreaded FOMO, so they effectively get a free insurance policy against recessions and falling stock markets.

Of course, past returns are not always indicative of future returns. But historically speaking, you could do a lot worse than piling into bonds when the yield curve inverts and waiting for market valuations to come down to reasonable levels.

So glad to see you've started a stack!

I don't see an email for you so I'll just say this here:

Your book and your writing changed my life in incredibly positive ways. It "came" to me at just the right time in my life. I think the book is a genuinely creative act in the "existential" sense and appreciate it as such.

I know that is weird for a non-economist (and non-professional) to say about a book about heterodox economics but you tied together a ton of threads that I had in similar ways and it was very comforting to see.

The stuff in the book about ideology, epistemology, and human psychology is great. To see you apply this to your discipline in similar ways to the way I tie it into my general life philosophy was awesome. I hope your editor did not try to dissuade you from including it.

I also hope that you eventually write a "broader" book (on something "wider" than explicit economics) and incorporate all these themes.

Thanks again for all your hard work.