A fever has caught on in Washington DC. It started out as a war fever, sparked by the Russian invasion of Ukraine. But it has been building on itself as the global order turns away from the United States. The last straw was the Saudi rejection of the Biden Administration’s request to delay oil cuts. This sent the Beltway buck wild, as the southerners say. In its frenzied state, DC is lashing out in ways that gravely threaten the future of the American economy.

Enter the Dragon

Washington is now looking for a fight. And it has found one it can pick with China over semiconductors. While the fight is an economic one, it is being portrayed by the White House as an existential battle between good and evil. National Security adviser Jake Sullivan was sent out to the podium to deliver the message and he pulled no punches.

The Peoples’ Republic of China’s assertiveness at home and abroad is advancing an illiberal vision across economic, political, security, and technological realms in competition with the West. It is the only competitor with both the intent to reshape the international order and the growing capacity to do it.

To counter this threat, the White House has passed legislation banning the export of American semiconductors to China. The justification for this is national security. Sullivan again:

These restrictions are premised on straightforward national security concerns. These technologies are used to develop and field advanced military systems, including weapons of mass destruction, hypersonic missiles, autonomous systems, and mass surveillance.

Yet semiconductors are not used in key military technologies that give China the edge over the US in the pacific theatre. The key weapon in this respect is the Chinese hypersonic anti-shipping missile, the YJ-21. The YJ-21 gravely threatens the carrier battle groups in the South China Sea that would be depended on if there were ever conflict over Taiwan. Recently The Washington Post has claimed that American chips are used in Chinese hypersonics, and this seems to be the driving motivation behind the recent chip ban.

It is unclear that this matters, however. Why? Because Russia seems perfectly capable of building hypersonic missiles without access to American technology. The 3M22 Zircon was first successfully launched in mid-2017 and looks pretty similar to the YJ-21. And while there have been reports that the Russian hypersonics are using Western technology, this seems highly unlikely. The Russians have been sanction-proofing their economy since 2014. If they are still reliant on unreliable external sources for the semiconductors needed to make key munitions they would be highly irrational. It seems much more likely that the Russians have worked out a go-around.

The evidence too seems to point in the direction that they do not need access to American technology. Since the start of the war in Ukraine, there have been report after report of the Russians running out of missiles due to the sanctions. Yet time and again, Russian hypersonic cruise missiles rain down on Ukraine.

If the Russians have figured out a way to build hypersonics without direct access to American technology, it should not be hard for them to share the needed the process with the Chinese. This is assuming that the Chinese even need external help with the technology. They probably do not.

Finally, imagine that the United States can, in fact, ban Russia and China from buying the semi-conductors needed for their hypersonic missiles. What will obviously then happen is that a black market will form. Russian and Chinese buyers will simply enter foreign markets and buy the semiconductors there under the pretext that they are being used for something else.

Suicide by Sanctions

The sanctions placed on American chip exports is going to wreak havoc on the American chip industry. There are a number of reasons for this. The first is simply that the ban will destroy Chinese demand for these products. China is currently the biggest market for American semiconductor exports, making up nearly 15% of the total market. With a large amount of revenue destroyed, expect CapEx in the industry to fall. The economist David Goldman has estimated that for every $1 the US government provides in subsidies to the semiconducter industry, $5 will be lost in revenue due to the bans.

America’s chip industry is already a laggard. Julius Krein has written a fantastic essay on the farce that was the CHIPS Act. Krein charts the trajectory of the CHIPS Act from a much-needed support pillar for the American semiconductor industry, to a bill that was torn apart by special interests, leaving a bad taste in the mouth of everyone who touched it. The export ban has taken a hammer to an industry that already needs government support but cannot obtain it due to dysfunction in DC.

Then there are the more micro-level impacts. One of the most interesting parts of the ban is that it places restrictions (a) on American citizens from working with Chinese and China-adjacent chip manufacturers and (b) on firms that use American technology in the manufacturing process of chips.

The latter ban is comical from an economics perspective. The incentive that it sets up is so glaring that an undergraduate economics student would be flunked for not spotting it: if restrictions are placed on firms that use American technology, firms will shy away from using American technology. Not only will the export ban harm the American semiconductor industry, it will also harm adjacent industries. As the American semiconductor industry wanes, the Chinese will be incentivised to rapidly create their own — and this is precisely the sort of project the Chinese excel at.

The restrictions placed on American citizens are almost as odd as the restrictions placed on American technology. They create enormous negative incentives for the semiconductor labour market. Days after the ban was announced American engineers were fired by Beijing companies. American engineers just became vastly less employable in the global market for semiconductors.

Imagine that you are a young aspiring engineer. Perhaps your parents are engineers who left a country where government interferes too much in business. You are inclined to go into the exciting semiconducter industry, or perhaps more generally into the tech industry. Then you hear that your cousin was just fired because the White House decided to engage in an arbitrary semiconductor ban. Your passport is a liability in the industry. Do you pursue this career path? Probably not. The export ban thus incentivises smart young people from shying away from the American technology sector.

The Technological Fallacy

While the chip ban may have been nominally undertaken as a matter of national security, it is hard not to see it as part of a larger trade war that the United States seem to be trying to wage against China since the Trump Administration. But the framing of the debate is topsy turvy. It has been since the start of the debate, which I participated in quite early on.

There are many people in policymaking who believe in a fallacy. The fallacy runs something like this: geopolitical strength comes from economic strength, and economic strength comes from technological innovation. The first part of this statement is correct. These days geopolitical power is only secondarily dependent on the size of one’s army. The size of one’s economy, and the capacity to trade with other nations, is much more important.

But the second part of the statement is completely false. Economic power flows from two key sources. One is the overall size of an economy. A very high GDP number indicates a very large amount of influence over other countries. Each dollar of GDP is a dollar of purchasing power. And as your favourite rapper will no doubt tell you: more dollars means more power, prestige and influence.

Does cutting-edge technology drive GDP? No. Or, at least, not primarily. In the long-run GDP is determined by two broad sources: growth in the labour force and productivity growth. Productivity growth is in part driven by technological development. But this does not necessarily mean cutting edge technological development. It typically means clever new uses of technology in the production process. It can also mean simply reorganising production processes in ways that increase productivity.

The second source of economic power is trade — or, more precisely, the ability to run trade policy on favourable terms for oneself. Specifically, power arises from being able to run a trade surplus with your rivals. If you run a trade surplus, then your rival is going into debt with you while at the same time you are selling them your product which in turn strengthens your domestic industry. The longer you run a trade deficit with your rival, the more they fall into debt with you — and the more power you wield over them.

China scores big on both counts. No matter what the technofantasists tell themselves, there is simply no way for the United States to diminish the overall size of the Chinese economy — short of nuclear weapons. But America could do something about the trade deficit it runs with China. The problem, however, is that the deficit has almost nothing to do with technology. China runs trade surpluses mainly because it produces relatively low-tech capital and consumer goods much cheaper than America can.

If the United States was really serious about diminishing its reliance on China, it would focus on reshoring this production — not on semiconductor bans. The best way to do this would be to run an import substitution policy and an industrial policy. The most effective apprroach to this would be to set up subsidies/incentives for specific businesses that the government wants to onshore. Probably the easiest way to do this in America today is to take advantage of the thriving and ever-flexible private equity industry.

Asymmetric Economic Warfare

The technophile might assume that hitting China with bans on high tech imports does more damage than China ever could. But this is again a fallacy. At best, the American ban will set Chinese technological development back a few years. But China have the potential to hit back harder — much harder.

This is due to what we have just noted: economic power flows from the absolute capacity to flood your rival with your output. Doing this makes your rival completely dependent on you at every level, while at the same time building up huge financial claims on your rival that you can use as leverage if they get uppity.

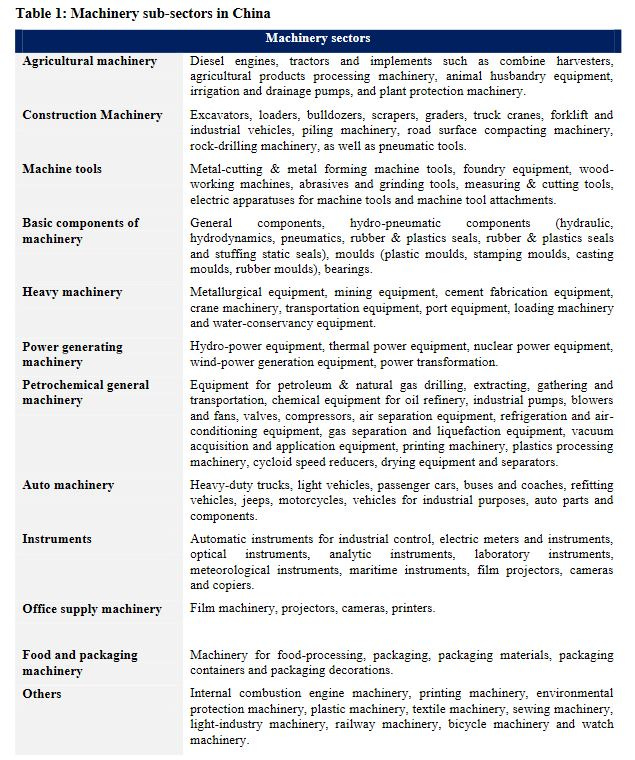

Many China hawks seem to assume that China merely provides the United States with cheap consumer goods. While this may have been true in the 1990s, it is far from the case today. Today China provides America with access to key capital goods. Capital goods are the goods that make other goods — think machinery, machine tools and so on. In America, China’s reach into this market is enormous.

In 2019, China exported around $191bn worth of capital goods to the United States. The table below — taken from this excellent study of China’s machinery sector — shows just some of the reach of China’s extensive machinery industry. Reading through this list you can imagine these products sitting in factories, on farms, construction sites etc across America and you realise just how dependent the American economy is on China.

What happens now if China decide not to send these goods? They would not even have to do so explicitly. They could just impose lockdowns on Shanghai to prevent shipments. Or they could target specific factories for partial closure due to COVID-19 restrictions.

If they don’t send the goods, American industry grinds to a halt. Factories stop production. Starved for spare parts, machinery falls apart. With industry slowing down, less consumer goods get made. Less consumer goods on the shelves means prices rise which means — you guessed it — more inflation.

There is also a national security question: how much does the US military rely on Chinese goods? Recent reports suggest that American F35 fighters source key parts from China. This is likely just the tip of the iceberg. Did Sullivan and the National Security folks model out the potential consequences of China deciding to starve the US military of key components? Real models. Models that track every component part that the US military relies on — not just stuff made in China, but stuff that is made using stuff made in China? I seriously doubt it.

In reality, the capacity for the United States to cause damage to China’s economy is minimal. They might be able to throw sand in the gears of China’s chip-sourcing for a few years. Perhaps this will give the United States a very short-term edge over China in cutting edge technology. But the Chinese are an adaptive people. They will overcome.

China, on the other hand, can grind the American economy to a halt by simply starving it of key capital goods exports. This would cause immense damage in the short-term, in the form of shortages and inflation. But it would also cause enormous damage in the long-term because it would produce rot in America’s industry as repairs, replacements and maintanence are deferred due to lack of spare parts.

Finally, there is the question of debt. The American debt and currency reserves that China holds are their economic nuclear weapon. China currently holds around $980bn worth of Treasuries and, although the exact figure is not known, probably around $3.5trn worth of US dollar currency reserves. The daily turnover in the global market for US dollars is around $6trn. If China went all in, liquidated their Treasuries and dumped their reserves, there would be an overnight increase in the number of US dollars available for purchase on the global market of around 40%. Such a dramatic increase would almost certainly crash the dollar and America could well spiral into a hyperinflationary collapse.

Unipolarity Corrupts Uniformly

Much of the problem with American policy is that it rests on an implicit assumption that America is so powerful that it can act unilaterally wherever it wants without incurring any consequences. This may have been true in the mid-90s. But it is absurd to believe that this is the case today.

DC policymakers are no doubt frustrated with what they see — correctly — as the emergence of a more multipolar world in recent years. This process has sped up immeasurably in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It appears that they now want to take action to rebalance the global order in their favour.

Some of us have been sounding the alarm on this for years. Yet those of us who have actually thought this through realise that America cannot simply dictate its way out of these problems. Bully tactics will only speed up America’s economic and strategic decline. Market traders will tell you to never bet against the trend. This is true also of major geopolitical shifts.

In the wake of America’s chip sanctions on China we are already seeing this play out. A few days after the sanctions, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz stated that decoupling from China was “the wrong answer” and announced an upcoming trip to Beijing. Dutch chipmaker ASML has long warned that sanctions on chipmakers are not viable, as has Japanese chipmaker Tokyo Electron. Recent reports suggest that Washington failed to convince their allies to take part in the sanctions and had to proceed unilaterally.

American leaders appear to think that key parts of the world economy should come to a standstill to ensure that the United States will maintain a technological edge for a few more years. This is bizarre coming from a country who has built its influence and prestige through global commerce. It appears to rest on the assumption that global commerce can stopped in order to freeze geopolitical relations and hold them in place as they currently exist. This is reminiscent of King Canute trying to control the tides.

If America wants to better deal with the emerging multipolar world it must use strategies different to those that worked in that brief phase, from the end of the Cold War until recently, when they sat on high as the reigning unipolar power. If American policymakers continue to pretend that this old world order still exists and act accordingly, they will only speed up the decline of their country. At a certain point — and it may not be too far off — the country will fall into terminal decline and there will be no coming back.

good one

hello good morning

My name is Nusratullah, my sincerity is sincere, I have contacted you from Afghanistan.

The situation in Afghanistan is very bad, people are being killed, girls' schools are closed, people are not given human rights, humanitarian aid is given to the Taliban, my education and that of all the children are being destroyed.

I hope from you to find a good way to leave Afghanistan, to leave Afghanistan and educate the children, make them live?!