I’ve been writing about supply chain and labour market disruptions and inflation for some time. I think that my essay for MoneyWeek in September can credibly claim to be one of the first pieces arguing that evidence was emerging that we were seeing supply chain and labour market issues due to the pandemic. Since then I have been writing pretty regularly on the topic over at UnHerd.

This week the debate went mainstream, with Fed Chairman Jerome Powell saying that the response to the pandemic is driving the shortages and the inflation and the effects were unlikely to be transitory. I pointed out over at UnHerd yesterday that Powell and his ilk likely think that this absolves them of responsibility for the inflation; they can shunt the blames onto the public health bureaucrats and hope that inflation will pass when the vaccines stamp out the virus. As I point out in my piece, at this stage there seems like literally no hope that the vaccines will stamp out the virus, so this passing of the buck is unlikely to work very well — either in terms of providing a solution to the inflation problem or in terms of absolving the central banks from responsibility.

As all this drama was going on within the institutions — and, it must be said, with the market response to these somewhat profound revelations about the present being surprisingly muted — the Bank of International Settlements published a nice paper discussing the supply chain problems. I thought it might be worth highlighting and commenting on some parts of this paper.

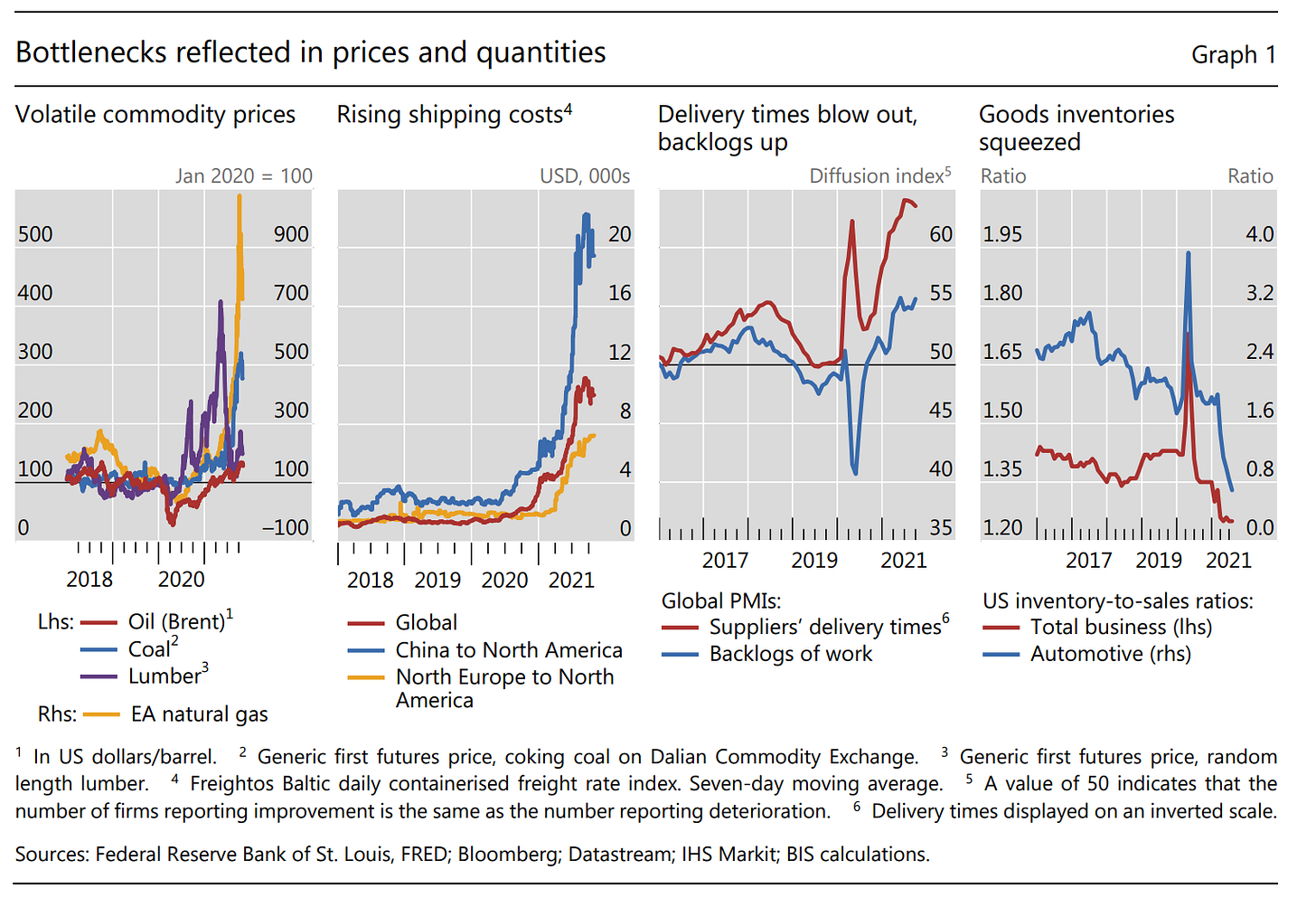

The first aspect they discuss is the bottlenecks that we have seen emerge in the global economy. The BIS authors share the following, rather nice series of charts.

The authors give a nice description of how the responses to the pandemic have led to these bottlenecks:

Pandemic-induced supply disruptions have clearly been a major cause of bottlenecks, especially in the early stages of the global recovery. Producers who had severed relationships with suppliers early in the pandemic found it hard to re-establish them when demand picked up. Asynchronous lockdowns disrupted shipping, while sporadic virus outbreaks led to further dislocations.

This has been the trigger. But there are other dynamics that have amplified the inflationary effects. One is the shift from service-oriented goods to manufactured goods during and after the pandemic. This is due to the fact that some services were cut off altogether and many that remain are less attractive than they were pre-pandemic — so consumer switch their income toward more ‘stuff’. The other dynamic that has amplified the inflationary effect is hoarding. Just as consumer hoarded toilet paper at the start of the pandemic, producers and distributors have tried to build extra inventory to deal with future shocks.

The authors also note that the crisis has been worsened by underlying structural features of the globalised economy:

the lean structure of supply chains… have prioritised efficiency over resilience in recent decades. These intricate networks of production and logistics were a virtue in normal times, but have become a shock propagator during the pandemic. Once dislocations emerged, the complexity of supply chains made them hard to repair, leading to persistent mismatches between demand and supply.

Another interesting thing that the authors highlight is that the inflation is, at least in its initial guise, a ‘trickle-down inflation’. It began in ‘upstream’ industries — that is, more basic industries at the base of the supply chain — and then has knock-on effects on industries and services that many of us have more day-to-day experience with.

This is all very interesting. But it can be used to draw erroneous conclusions. The authors have almost completely focused on the production sector. In doing so, they have correctly identified the spark that started the inflationary fire. But this leads them to assume that once the production sector gets better adapted — specifically through higher rates of investment — the supply chain issues will dissolve.

But this is not how inflation ‘sticks’. For inflation to stick, you need labour market disruptions. And boy oh boy, have we seen some dramatic labour market disruptions in the past few months — everything from people dropping out of the labour market to vaccine mandates that ‘lock out’ workers to mass waves of reverse migration due to anticipated travel disruptions and stay-at-home orders.

The labour market is in an utterly desperate state. Does it look set to get better? No. The United States seems set on a path to further ramp up restrictions. Many European countries seem to be moving in a direction of rendering unvaccinated citizens unable to participate in public life — and note that 30-40% of their populations are unvaccinated!

Since about April of 2020 I have been of the opinion that trying to understand economic dynamics in this brave new world without taking long-term, evidence-based views on the trajectory of the pandemic and, especially, the public health response is the equivalent of trying to understand the anatomy of a dog by carefully examining a frog.

This opinion has stood up remarkably against the test of time. But it has never been popular. The default position of most commentators and observers lies somewhere in between “the effects of the public health measures on the economy are minor” and “there is no need for us to concern ourselves with these things as the public health mandarins have it all figured out”.

These are simply blindspots. And they are rapidly coming to a head. At some point those concerned with economies and with markets are going to have to reckon with these effects. More worrying still, they are going to have to reckon with the spectacular failure of the public health bureaucrats in trying to control the virus — and the destructive spiral that this has produced in our politicians and our leaders.

If and when the vaccines fail this winter, the politicians will know nothing else but to double down — this is already happening in central Europe. And when they double down, the economic consequences will likely get worse — or, at very least, will not get better. It’s going to be a long, dark winter.