Boris Johnson has dropped out of the leadership race in Britain. Word on the street is that this means that Rishi Sunak has all but gotten the job. Sunak has long been the City of London’s candidate, having held a career in finance before he became an MP. He started as an analyst at Goldman Sachs and then moved into hedge funds. By all accounts, Sunak is a smart chap who understands markets.

Already the chatter has started that Sunak’s tenure is going to be less a government than a transitionary period where Britain enters into receivership. Sunak’s rule will therefore resemble many of the ‘technocratic’ governments that we have seen pop in and out of existence in the Eurozone since the debt crisis of 2011. Yet, Britain’s time in the debtor’s prison will look very different to what happened in Europe in key respects.

This is because the Eurozone crisis was not really a debt crisis per se. Rather, it was a crisis generated by the lopsided structure of the monetary union itself. Within any monetary union there are always stronger and weaker players. For example, in the United States, the economy of Texas is far more powerful than the economy of Louisiana. And while various states can get into trouble when issuing local bonds, most of the borrowing takes place at the Federal level.

The Eurozone crisis was, in truth, the awakening of the Europeans to the fact that if they wanted a monetary union they would also need to have a guarantee on borrowing by various countries at the Federal level. This was eventually given when the ECB, under the tenure of Mario Draghi, famously stated that it would do “whatever it takes” to underwrite the sovereign debt of various European countries. It is in this context that we can understand the type of austreity that was imposed on the poorer countries.

In the European debt crisis, austerity was a policy choice. The deal that the poorer countries made with the richer countries was that the poorer countries would try to make themselves more competitive through austerity if the richer countries signed off on the backstop by the ECB. Whether this austerity was wise or not is a different question — I think that it was counterproductive and has given rise to growth stagnation in the Eurozone since — the key point is that it was a choice made by politicians that could, in theory, have been made differently.

What is about to happen in Britain is altogether different. Sunak and his government do not get to sit around a table of politicians in other countries to hammer out a deal. Rather, they must go to the negotiating table with the markets themselves. Britain’s crisis is a true balance of payments crisis. Due to the high energy prices caused by the war and the sanctions, Britain needs to borrow more than it can in the international capital markets. This means that the Sunak government will have to try to jump through hoops to please these markets — if indeed the current situation entails that it is possible to raise this borrowing. If Sunak and company cannot get the money in the door, sterling will fall and British living standards will fall with it.

Britain’s crisis is also different from emerging markets that often experience similar problem. This is because emerging markets balance of payments crises are typically crises generated by the country in question issuing foreign currency debt that it can ill afford. Argentina, for example, has a terrible habit of issuing USD-denominated bonds that it cannot realistically pay back. This gives the emerging market country experiencing the crisis another option: the default or the haircut. That is, the country in question can default on part or all of their foreign currency debt.

But Britain’s problem is not that it has issued foreign currency debt. It’s problem is that, until recently, it could convince foreigners to hold sufficient amounts of domestic currency debt (and other assets) to finance the current account deficit, but now that deficit is reaching levels that require more financing then is realistic. So, there is no option on the table for Britain to default. A de facto default would, in fact, just entail allowing sterling to adjust, import prices to skyrocket and living standards to fall.

Of course, there are other tools in the toolbox to keep sterling stable. The most obvious is the interest rate set by the Bank of England (BoE). A higher interest rate will make British debt more attractive to foreign investors and so should, all else equal, attract more foreign capital into the country. That is the macro 101 view, anyway. But it is not without faults.

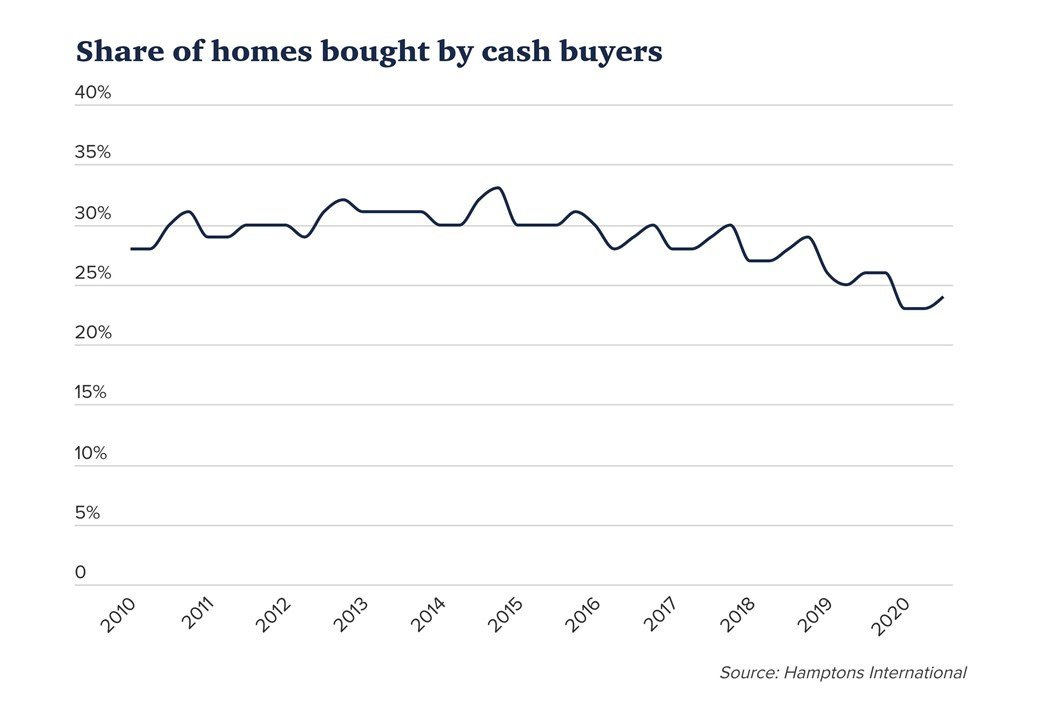

This is because one of the attractors of foreign capital in Britain is the British, or, more precisely, the London property market. The property market is only attractive when foreign investors think that their asset is going to rise in value. Yet high interest rates could squash the British property market. This is because, while the UK property market may have a very large amount of cash buyers, these cash buyers are still in the minority.

Anywhere between 70% and 75% of home buyers are mortgage buyers. Mortgage buyers rely on low interest rates to take on mortgages. So, if rates rise too much, the sector of the property market that does the heavy lifting will collapse.

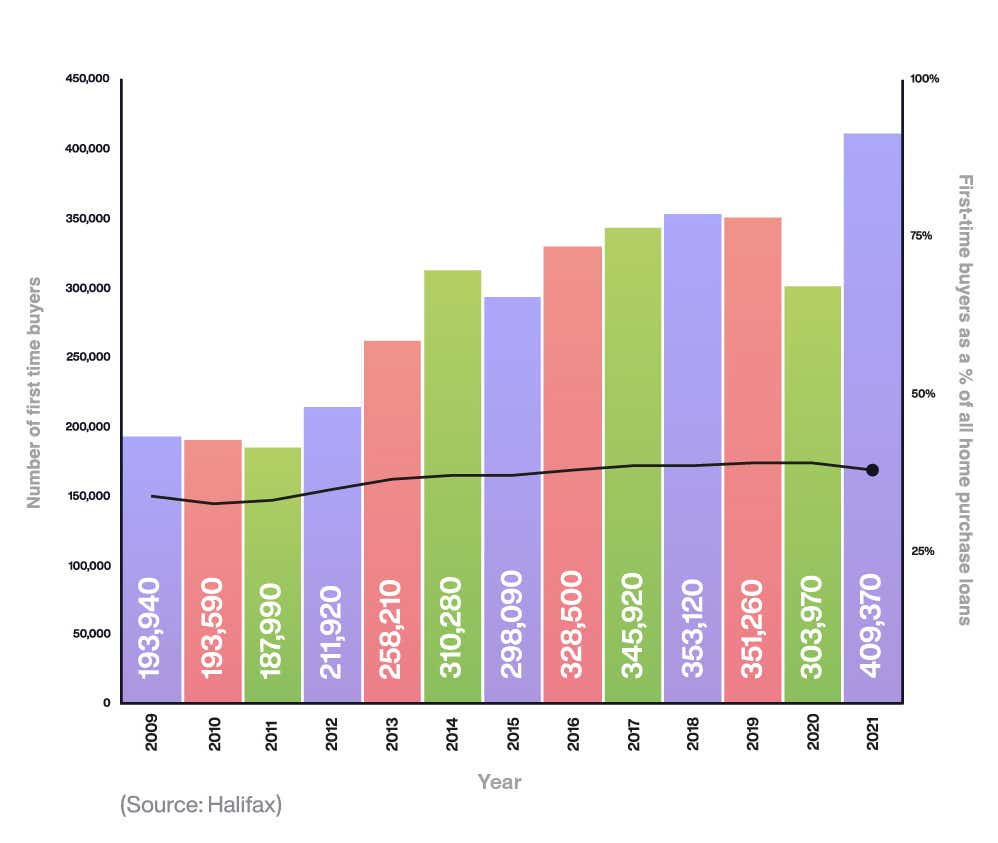

This is especially so because policy in the UK for the past few years has been to try to coax first-time buyers into the market.

This policy has been justified by the government saying that young people should own their own homes. But it has the added bonus of buttressing the domestic housing markets. Let’s just say that property developers and foreign property investors have never objected to this policy!

Yet first-time buyers are particularly sensitive to interest rate hikes. Given that they now make up around 40% of the mortgaged-buyer market. This makes the British property market even more sensitive to rate hikes.

This probably explains why the BoE is currently fighting the markets on rate hikes: the Bank senses how hard it could hit the domestic property market. And since the property market is a key receiver of foreign capital inflows, this could put further downward pressure on sterling.

The impending British crisis therefore looks extemely unique. But probably not in a particularly good way. There is no simple solution to this crisis. And the most likely outcome is that Britain will be forced to muddle through.

"There is no simple solution to this crisis. "

There is. We stop seeing the exchange rate as a target and start seeing it as a safety valve. The UK doesn't have to 'attract foreign capital' at all. As with 'government borrowing' it is a balancing item that happens automatically if cross border transactions happen at all. The exchange rate is an emergent expression of the desire of the rest of the world to sell things to the UK which, given there isn't an alternative source of spare demand, they either do or they don't sell their output.

What we do is dump the mainstream belief system and start looking at imports functionally. There are discretionary imports and non-discretionary imports (food and fuel primarily). The UK is price taker on non-discretionary items, but price maker on discretionary items (or they wouldn't be discretionary).

The cost of the energy cap could be allocated to discretionary imports in a hypothecated manner, and the real terms of trade loss would then be absorbed by those who consume and sell discretionary imports. Far better them than young people trying to set up home with a mortgage.

Rather than trying to buy more financial exports with interest rate changes, it is better to reallocate the loss in the import space from discretionary to non-discretionary which then increases the braking effect of a currency rate change and should mean it doesn't have to go quite as far to rebalance the flows.

An excellent summation, thank you very much. In other words the UK property market will gradually decline, the British standard of living will fall, and a slow economic depression will ensue. All, as predicted in my Chapter 13. An understanding of history makes these projections realistic. We are indeed in the Fourth Turning and it will unfold as it has in the past.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358117070_THE_FINANCIAL_JIGSAW_-_PART_1_-_4th_Edition_2020

AND

https://austrianpeter.substack.com/p/the-financial-jigsaw-part-2-the-end?s=w